Metal detecting is always a lottery. No one knows what awaits us in the next hole. The finds can be absolutely anything, with no limits. And, of course, some are quite gruesome. Like these… Do you know what the Teeth of Waterloo are? It’s very interesting!

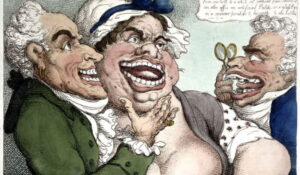

The Battle of Waterloo in 1815, which marked the definitive defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte, left a profound impact not only on European politics but also on a strange, lesser-known chapter in dental history. On the battlefield, nearly 50,000 soldiers from both sides perished. However, amidst the tragedy, a macabre practice emerged: the extraction of healthy teeth from the dead to make dentures. These teeth, often called “Waterloo teeth,” were highly prized and became a significant part of dental prosthetics during the 19th century. The story of Waterloo teeth sheds light on the grim realities of medical practices at the time and offers a glimpse into the resourcefulness of a growing industry.

Before modern dentistry, the demand for dental replacements, particularly dentures, was high due to widespread tooth decay, poor hygiene, and lack of proper dental care. Wealthier individuals, who often suffered from severe dental problems, were willing to pay a premium for solutions that allowed them to eat and speak comfortably while maintaining a semblance of normal appearance. However, finding suitable materials for dentures posed a significant challenge. Human teeth, harvested from healthy individuals, were considered the best option, as they were more functional and less likely to be rejected by the body than alternatives like wood, ivory, or animal teeth.

The battlefield after Waterloo became a source of these precious teeth. Soldiers and scavengers alike collected the teeth of fallen soldiers, particularly focusing on young men who had healthy teeth due to their age and the relatively short duration of their service. Once extracted, these teeth were cleaned and shipped to England, where they were fashioned into dentures. It is important to note that the teeth from Waterloo were not the first to be harvested for this purpose, but they became iconic due to the scale of the battle and the subsequent availability of a large number of high-quality teeth.

These dentures, commonly referred to as “Waterloo teeth,” became synonymous with any dental prosthetics made from real human teeth, regardless of their origin. Over time, the term extended to cover all such prostheses, reflecting the popularity and widespread use of this grim resource. For many, wearing “Waterloo teeth” was a status symbol, as it indicated that the dentures had been made from human teeth rather than less effective materials. Ironically, these prosthetics, created from the remains of the fallen, often ended up in the mouths of wealthy civilians far removed from the horrors of war.

This practice, while disturbing by modern standards, was born out of necessity. Medical and dental science were still in their infancy, and the use of human teeth was seen as a practical solution to a widespread problem. The legacy of the “Waterloo teeth” reminds us of the often gruesome realities of the past and the lengths to which people were willing to go to address basic human needs such as eating and speaking. Today, advancements in dental materials and hygiene have rendered such practices obsolete, but the story of Waterloo teeth remains a fascinating chapter in the history of medicine and dentistry.

The author of the text is the commenter Gold Searcher. This was, in fact, a comment left on the article. By the way, check out other comments with photos—some of the teeth finds are quite funny (and at the same time, make you think).

While metal detecting, I have come across teeth. I didn’t pick them up. And I always wondered, what if the teeth were gold? Would I still not pick them up? What’s the difference?

Very interesting.

O tempora, o mores!